European pro-trade policy likely to stay in place after the European elections

Summary

Preliminary results from the European elections indicate that eurosceptic parties have won seats in the European Parliament, but not enough to dictate policy

The election result has little influence on the EU’s external trade agenda because there is division between eurosceptic parties when it comes to support for free trade

- In the coming months a decision will have to be made about three top positions that become vacant at the European Commission, the European Council and the European Central Bank

Preliminary results of the European elections show that eurosceptic parties have won a greater share of seats in the European Parliament (EP). The elections took place between 23 and 26 May 2019 across 28 European countries that are a member state of the European Union. Voters in each member state vote for national parties and this in turn determines the number of seats these parties obtain in the EP. Each member state has a fixed number of seats in parliament that depends on the relative size of their population. European Parliament elections take place every five years and some major changes have occurred since the last vote, which was held in May 2014, most notably the announced exit by the United Kingdom from the EU. However, with Brexit delayed until late October this year, the UK still participated in the 2019 EP elections. Because the UK is still a member of the EU the total number of seats in parliament remains at 751 (whereas a Brexit would have caused the number of seats to decline to 705).

The European Parliament has the power to legislate, which is a responsibility that is jointly shared with the European Commission – the executive arm of the EU. The parliament also supervises spending by the EU and it adopts the annual EU budget. Furthermore, it plays a crucial role in supervising the European Commission. If two-thirds of the parliament votes in favour of a motion of censure against the European Commission, the entire Commission is forced to resign.

Eurosceptic parties gain influence

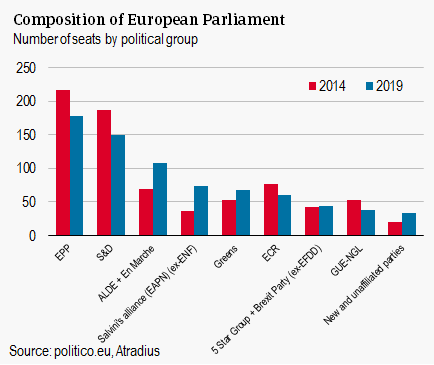

Preliminary results indicate that eurosceptic parties have gained close to a third of the total vote. During the 2014 elections, the eurosceptic political groups got 28% of the vote. However, it is difficult to make an exact comparison with 2014, because the landscape of political groups has shifted with the creation of the new right-wing nationalist European Alliance for People and Nations (EAPN). EAPN, which was founded by Northern League leader Matteo Salvini, will lead to the dissolution of a number of other eurosceptic groups. The EAPN should be seen as the incarnation of what was previously the far-right nationalist Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF) but is likely to draw parties from other political groups such as EFDD as well.

Eurosceptic parties are critics of the European Union (EU) and European integration. They range from ‘soft’ eurosceptics who oppose some EU institutions and policies and seek reform to the hard-liners who oppose EU membership outright. Eurosceptic parties can mainly be found in four political groups (political families that represent ideologically aligned members of parliament). On the far left, the European United Left-Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL) contains a mix of 'soft' and 'hard' eurosceptic socialist and communist parties. On the right, there are the 'soft' eurosceptic European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the far-right nationalist European Alliance for People and Nations (EAPN) founded by Northern League leader Matteo Salvini. Finally there is the anti-establishment group led by Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party and Italy’s Five Star Movement.

The greater influence of eurosceptic parties comes at the expense of the current governing bloc that consists of the Christian Democrat European People’s Party (EPP), the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and the liberal-centrist Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE). According to the elections results these three parties have obtained 437 out of 751 seats available. The previous number of seats was 472 (63% of the total versus 58% at present).

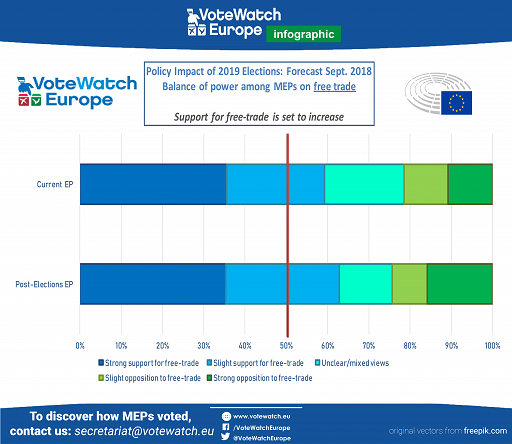

What binds eurosceptic parties is their dislike of the European Union and their resistance to further European integration. On many important issues, varying from immigration to fiscal discipline, however, the eurosceptics are strongly divided. With respect to trade, there is no unified position either. Several anti-EU parties either do not oppose free trade outright (Alternative for Germany) or are among its most stable supporters (Law and Justice, or PiS). Some others, such as the Five Star Movement and Front National are very critical of the EU’s external trade agenda. There is also no overall shift to be expected in the balance of power in the European Parliament towards trade-related decisions. According to VoteWatch, the share of parliament that leans towards supporting free trade is unlikely to change much after the European elections. They projected in September 2018 that 63% of members of parliament support free trade compared to 59% now.

With respect to preparing and negotiating trade agreements, the initiative is not with the European Parliament, but with the European Commission. Parliament may submit comments and proposals and is consulted during negotiations with a trade partner. However, on the final agreement it can only cast an accept/reject vote. While eurosceptic parties can try to slow down the EU’s external trade agenda, they will not be able to fundamentally change the course of trade policy. Besides lacking a majority in parliament, there is too much division between the eurosceptic parties for this to take place.

Important nominations for the European Council and the European Commission

Besides deciding the composition of the European Parliament and the direction of policymaking, the European election result may also play a crucial role in determining the leadership of the European Council and the European Commission. Current European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker is retiring in November 2019. The Lisbon Treaty states that the European Council should put forward a candidate for the Commission president to the EP. The parliament must then approve the appointment with a majority vote.

Prior to the European election each political group has put forward a lead candidate and convention dictates that the group winning the most seats will see their candidate becoming the next Commission President. Since EPP has remained the biggest political group after the 2019 elections, their lead candidate Manfred Weber (a German Christian-Democrat) is the favourite to become the next European Commission president. The second-largest political group S&D has nominated Dutch Social-Democrat Frans Timmermans. While Manfred Weber is the frontrunner, the nomination of a Commission president is highly political, and the more fragmented political landscape will make the outcome of the nomination process more uncertain. However, it is unlikely that eurosceptic parties will be able to influence the decision on who is to become the next Commission president, since the current governing bloc retains its majority.

Another top position for which a vacancy will open is that of European Council president Donald Tusk, who is retiring in November 2019. The European Council consists of the heads of state or government from the EU member states, along with the presidents of the European Council and European Commission. The European Council elects its own president via a majority vote. Like with the Commission president, the appointment of a Council president is a strongly politicized process. The largest party in the European Parliament – which after the 2019 elections is again the EPP - traditionally has the best chance of providing the next Council president. Both previous Council presidents, the Herman van Rompuy and incumbent Donald Tusk, were former prime ministers and both are from parties that sit as part of the EPP.

The new ECB president

In October 2019, a decision will have to be made on who will become the successor to Mario Draghi as chairman of the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB president is elected via a majority vote in the European Council the Germany indicated in August 2018 that it will favour the presidency of the European Commission over that of the ECB. In keeping with the long tradition of horse-trading within the EU, a German Commission presidency might involve a compromise with the French, which would mean France gets the presidency of the ECB. France’s frontrunner is Francois Villeroy de Galhau, the governor of the Bank of France (the central bank). Other contenders for the top ECB job are Erkki Liikanen (Finnish) and Philip Lane (Irish), both former central bank governors. Draghi has built a track record of willingness to support the economic recovery with easy monetary policy. Neither successor is expected to substantially deviate from this track record.

Theo Smid, economist

theo.smid@atradius.com

+31 20 553 2169

Documenti collegati

164KB PDF